Picture: U.S. Navy

This is part two of an analysis of Russia's Oreshnik medium- to intermediate-range ballistic missile, demonstrated for the first time during the November 20–21 attack on Dnipro.

Last week, I explored the missile’s implications for the past and future of arms control between NATO and Russia. You can read the previous post here. This analysis focuses on what the Oreshnik means for NATO's missile defense posture in Europe.

What do we know about the Oreshnik so far?

Here’s a quick recap along with additional information released since last week.

Oreshnik is a new missile system based on the Russian RS-26 Rubezh (SS-X-31), which was developed between 2008 and 2018 but mothballed before reaching full operational capability.

According to Ukrainian assessments, development of the RS-26 continued under the new designation “Kedr,” reportedly describing the same capability as the Oreshnik. Like the RS-26, the Oreshnik is almost certainly a solid-propellant, two-stage missile, with stages identical to the first two used in the RS-24 YaRS ICBM.

While Putin described the missile as a medium-range capability, it likely falls within the intermediate-range spectrum (3,000–5,500 km) and could potentially engage targets at the lower bounds of the intercontinental-range spectrum (>5,500 km), depending on the trajectory flown. Perhaps the most notable feature demonstrated by the Oreshnik was its non-nuclear MIRV capability, enabling it to carry multiple warheads that can be independently targeted.

Although MIRV technology is common in nuclear missiles, the Oreshnik is the first and currently the only operational ballistic missile confirmed to be equipped with a non-nuclear MIRV payload (there are claims that some Iranian MRBMs may be equipped with MIRV technology). That said, the missile's exact payload configuration remains somewhat unclear. Reports suggest the Oreshnik carries six re-entry vehicles, each equipped with a non-nuclear warhead. According to HUR reports, each of these warheads contains six inert submunitions, though it is unclear what these submunitions are (dummies, weight simulators, penetration aids, something else?). Conventional explosives are very likely not involved.

If these reports are accurate, this suggests that Russia successfully developed a dedicated payload system for the missile—something I initially considered unlikely given the engineering challenges involved and Russia’s demonstrated lack of innovation during the war, particularly in the missile domain. However, the warhead system is likely of a rudimentary nature and, as evidenced by the attack, lacks lethality due to the missile's poor accuracy.

Additionally, Ukrainian sources reported that the terminal velocity of Oreshnik’s warheads exceeded Mach 11 (3.7 km/s). This indicates the missile likely followed a high and steep trajectory, consistent with its range limitations and the reported launcher position at the Kapustin Yar missile training and test site, approximately 800 km from Ukraine.

Oreshnik’s trajectory and speed profile differ significantly from those of other Russian ballistic missiles used extensively, such as the 9M723 short-range ballistic missile of the Iskander-M complex and the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile.

The 9M723 and Kinzhal remain within the atmosphere for most or all of their flight and decelerate to below hypersonic speeds during their descent. However, both systems are likely significantly more maneuverable during their terminal approach compared to the Oreshnik’s re-entry vehicles which likely lack thrusters or aerodynamic surfaces to effectively maneuver.

Implications for missile defense

Nevertheless, the Oreshnik represents a challenge to NATO’s missile defense architecture. The missile’s flight regime means that widely used NATO ballistic missile defense systems, most notably the MIM-104 Patriot but also the Franco-Italian SAMP/T, offer only limited defense against this missile system.

Unlike shorter-range ballistic missile systems, Oreshnik constitutes primarily a medium to intermediate-range ballistic missile that approaches its targets from very high altitudes (well outside the atmosphere) and closes in with a comparatively high terminal velocity. Neither Patriot nor SAMP/T are optimized for this type of threat. “Optimized” is a keyword here. These systems may still be able to provide some level of limited protection, just not very effectively.

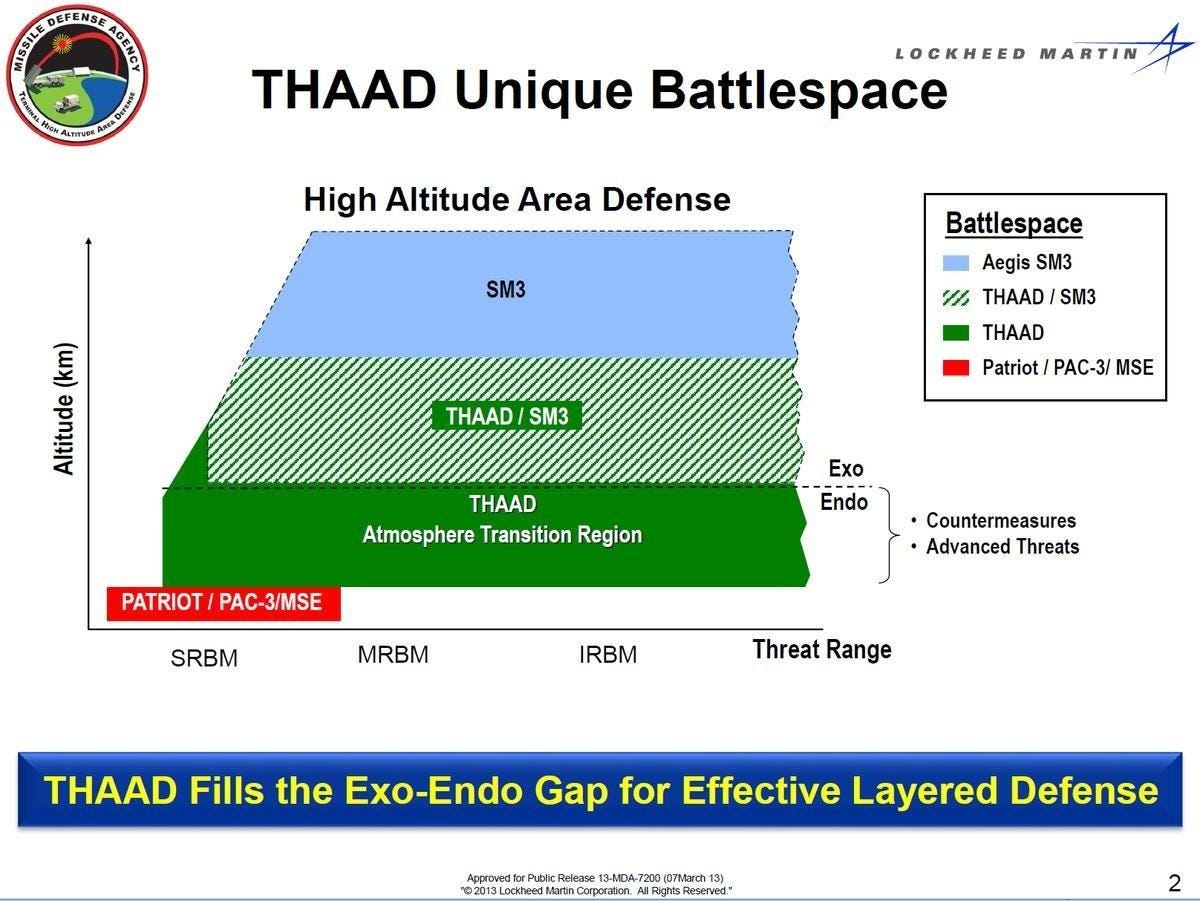

Effectively defending against ballistic missiles like Oreshnik therefore requires other types of missile defense systems that intercept missile threats higher in the atmosphere or outside of it (see the graphic below).

Examples include the American SM-3, which can be launched from NATO surface vessels or land-based Aegis Ashore sites, as well as Talon interceptors used in THAAD (which is currently not deployed to Europe). Another missile defense capability that could likely counter the Oreshnik is Germany’s Arrow 3 ballistic missile defense system, expected to reach initial operational capability by late 2025.

As outlined above, given that the Oreshnik’s MIRV payload likely has limited maneuverability—at least compared to aeroballistic missile threats like the 9M723 or Kinzhal—intercepting its warheads should be relatively straightforward. The greater challenge is likely the sheer number of warheads a single Oreshnik can deliver, even if they are relatively rudimentary. This could lead to NATO states depleting their missile defense interceptors quite rapidly.

This being said, it’s important not to overreact to this new threat. Moscow likely has a limited capacity to field Oreshnik ballistic missiles, as its missile production capabilities are already operating at maximum capacity. Any Oreshnik missiles currently in Russia’s arsenal are almost certainly not newly produced but rather reinstated and modified RS-26 missiles.

This suggests that until Russia can establish a production line for Oreshnik missiles, the potential depth of its arsenal will depend on the number of RS-26 early production units held in storage. While it is challenging to estimate these numbers, it is probably reasonable to assume there are no more than 20–30 missiles.

As such, the primary ballistic missile threat from Russia will continue to come from endo-atmospheric short- and medium-range aeroballistic missiles like the 9M723 and Kinzhal, which have dedicated production lines and are manufactured in substantial numbers. Frantic revisions to NATO’s missile defense plans and procurement projects are therefore neither necessary nor warranted.

Furthermore, there might even be an argument for disregarding the Oreshnik threat altogether. The missile’s inaccuracy, combined with the low lethality of its inert kinetic energy projectiles, means Russia would need considerable luck to achieve critical hits on key targets. The best course of action, therefore, might be to ignore incoming Oreshnik threats and conserve limited interceptor stockpiles for higher-value targets.

Unfortunately, there are two problems with this approach.

First, is it indeed smart to rely on the adversary not getting lucky? Military prudence would suggest otherwise. Second, Oreshnik is dual-capable, meaning that theoretically, any missile launched could carry a nuclear payload and must be treated as a high-value target. In practice, context clues—such as the stage and intensity of an escalating conflict—can provide insights into whether the missile is likely armed with a nuclear or conventional payload, though certainty is difficult to achieve. Military prudence would therefore again dictate engaging most if not all Oreshnik missiles. Note that this “dual-capability” issue is not exclusive to Oreshnik and also applies to the 9M723, Kinzhal, and many other Russian missile systems.

As a result, even though Oreshnik is not the most lethal weapon in Russia’s ballistic missile arsenal—far from it—, it could play a disruptive role in NATO’s missile defense planning by depleting NATO’s higher-echelon missile defense assets relatively early in a conflict. As such, while overreacting to the missile is not appropriate, Oreshnik poses a distinct type of challenge that cannot be fully ignored.

Thank you for yet another valuable article. Considering how sluggard European countries and the US have been in increasing missile defence system & interceptor production capabilities and not letting UA strike at launch sites directly with western ordinance.. ..these are not unreasonable concerns.

Just a crazy idea, but why not, for once, Europe tries to take the initiative? What about saying "oh, we are really impressed by the capabilities of Russian nuclear forces. Sadly, it forces the EU to develope a independent nuclear deterrence, and deploy IRBM with nukes in Finland, Poland, the baltic states and so on. In the same way we will establish a missile defence system to try to counter such a formidable adversary. Oh, and we fully support Ukraine joining NATO". This part must not even be true, but let's Putin think about the possibility. Meanwhile, EU should start flooding russian and bielorussian (specially Bielorussia) social networks with an information campaign denouncing the corruption of their respective governments, what a wonderfully life would be for both countries joining EU and supporting any internal opposition with money and media coverage.

I know it's not going to happen, but it would be nice to see EU doing something proactively and not only sending deep concerned speeches as a reaction to Putin new atrocities. .